The Persistent Protein Myth

The narrative that protein, particularly from animal sources, is harmful to health is a tale as old as time—or at least as old as modern dietary guidelines. Recently, sensational headlines claiming that high protein intake is linked to increased heart disease risk have once again flooded our newsfeeds and screens. These claims are not only alarmist but often misleading, ignoring the nuances of nutritional science. This article will dissect these claims, examine the underlying studies, and offer a balanced view on protein consumption and heart health.

The Problematic Headlines

The New York Post recently published an alarming article titled “You might be eating an artery-damaging amount of protein, new study warns,” citing a study from Nature Metabolism. The study claims that excessive protein intake could harm your arteries, suggesting that ramping up protein for metabolic health isn’t a straightforward benefit as it could lead to vascular damage. This stark warning comes from Babak Razani, a professor of cardiology at the University of Pittsburgh, who emphasizes the potential dangers of high-protein diets.

This article emerges shortly after a similar piece by Vox, which perpetuates the same protein paranoia by asserting that people are simply consuming too much protein. I delved into this article in greater detail in episode 71 of my podcast. Unsurprisingly, it concludes with a familiar prescription: reduce animal protein intake. This recommendation is accompanied by stark warnings of premature death for those who fail to comply, further stoking fear without offering a balanced perspective.

Unpacking the Study’s Claims

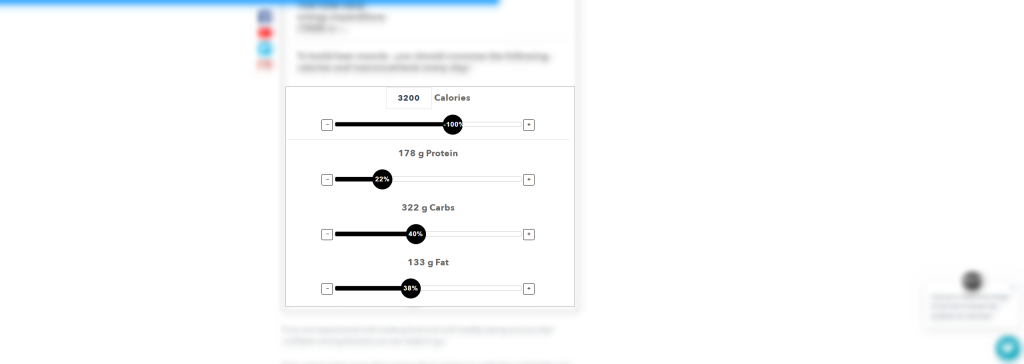

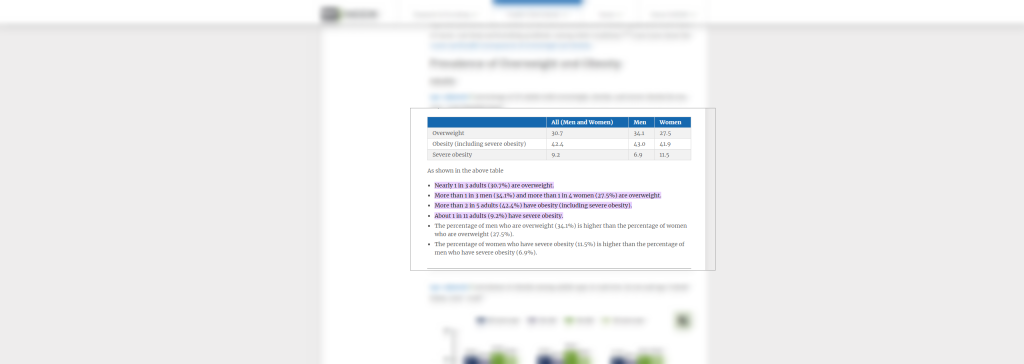

The study highlights that a significant portion of Americans, nearly a quarter, consume over 22% of their daily calories from protein, primarily animal sources. This statistic portrays as a risk factor for heart disease, yet the study does not address the broader context of overall diet quality and lifestyle factors that are equally, if not more, crucial to cardiovascular health. To the average person, a protein intake of 22% of daily calories might seem excessive. However, for those focused on longevity, health, muscle gain, and resilience, this level likely falls short of the recommended 1 gram of protein per pound of bodyweight—a target that effectively supports these goals. Furthermore, maintaining a higher protein intake is a proven strategy to reduce overall fatality rates, highlighting its importance beyond just muscle building.

Even when someone is consuming 22% of their calories from protein, it’s often because they are consuming an excess of overall calories, where the protein content incidentally aligns with their high caloric intake. The real issue for most of the population isn’t necessarily a high-protein diet, but rather the surplus of unnecessary calories that accompanies it. This scenario underscores the need for a balanced approach to nutrition that prioritizes not just the quantity of macronutrients, but the overall quality and caloric appropriateness of the diet.

There’s an amusing meme circulating that highlights a peculiar overlap: one article claims that only 12% of people are purchasing the majority of red meat, while another states that merely 12% of the US population is metabolically healthy. This seems to reflect a kind of Pareto distribution at play. Similarly, it’s reported that 25% of Americans get at least 22% of their calories from animal protein, yet nearly 73% of the nation is overweight. One might then wonder about the metabolic health of the remaining 27%—the setup almost seems like a joke ready to write itself. While we know correlation does not imply causation, these statistics certainly offer a humorous perspective to ponder.

The Misleading Nature of “Agendacles“

The term “agendacle” vividly captures the essence of agenda-driven articles that selectively use data and research to support predetermined conclusions. These articles typically rely on mechanistic studies, which may only reveal a fragment of the bigger picture, or on research conducted in cell cultures or on animals, which researchers cannot straightforwardly apply to humans without more comprehensive studies.

Frequently, these articles culminate with bold claims that, upon closer examination, tend to promote a specific theme or solution. This solution often aligns neatly with the narrative they’ve constructed throughout the piece. Given the nature of the discussion in this article, it’s reasonable to infer that their proposed “solution” likely advocates for reducing animal protein intake in favor of plant-based alternatives, echoing a common theme in similar agendacles. This not only aligns with a broader dietary shift being promoted in various health narratives but also taps into ongoing debates about sustainability and ethical eating.

Mechanistic Studies vs. Human Studies

To put it simply, mechanistic studies aim to understand a specific process or action at a highly detailed level, often examining just one step in a complex sequence. For instance, such studies might suggest that a particular function observed in a cell (let’s call this step 1) leads directly to a health outcome in an entire organism (step 7). However, drawing such direct lines without considering the myriad intervening factors—such as interactions with other biological systems, environmental influences, and genetic variations—is overly simplistic and potentially misleading.

Mechanistic studies provide valuable insights but are just the beginning of a much longer process of scientific inquiry. They are preliminary steps that should not be taken as conclusive without further testing in real-world conditions. For example, resveratrol, found in red wine, has shown health benefits in cell studies, just as glutamine has been found to be neurotoxic in similar studies. Yet, these findings do not hold up under broader human studies.

The Amino Acid Boogeyman

This brings us to the current discussion: according to recent research, leucine, which is rich in animal-derived foods like beef, eggs, and milk, is supposedly a major factor in abnormal macrophage activation and increased atherosclerosis risk. This has once again cast animal foods as the villain in the narrative of dietary health.

Dr. Babak Razani, commenting on these findings, suggests that simply increasing protein intake without considering the diet as a whole might be problematic. He advocates for balanced meals that do not exacerbate cardiovascular conditions, particularly in those at risk. Razani’s remarks further highlight presumed differences in how plant and animal proteins impact cardiovascular and metabolic health, suggesting a bias towards plant-based diets.

The notion of a “balanced diet” is complex and highly individualized. It’s a lifelong process of personal experimentation, and no universal solution fits everyone. Claims to the contrary often carry an underlying agenda. In this instance, the push towards plant-based diets seems apparent. It’s crucial to recognize that every dietary adjustment comes with its advantages and disadvantages. Striving for a so-called perfect diet is an unattainable goal—a nutritional “unicorn” that doesn’t exist. Instead, a more realistic approach is to tailor dietary choices to one’s specific health needs and lifestyle, acknowledging that perfection is an illusion and balance is key.

The Flawed Rodent Data

Further complicating the narrative, the rodent studies mentioned often use models that are genetically predisposed to high cholesterol and heart disease, such as ApoE knockout mice. This setup nearly ensures the development of heart disease, skewing the results and potentially exaggerating the role of protein in cardiovascular risk. Such studies are instrumental in the early stages of research but must be followed by more comprehensive human trials to draw relevant conclusions for dietary guidelines.

What About Human Studies?

We then progressed to human studies, examining two distinct groups. One group consumed protein shakes, either low (10% kcal from protein) or high (50% kcal from protein) in a fasted state, while the other group ate meals with 15% and 22% kcal from protein. This approach allows us to isolate the effects of protein in a controlled environment with shakes and in a more typical dietary setting with meals. Notably, the protein shakes used, such as Boost Protein—which lists water, corn syrup, and various oils before soy protein isolate as its primary ingredients—may not represent the ideal source of protein for studying its effects.

In these human trials, a short-term activation of mTOR followed meals, which some interpret as detrimental to heart health. However, this perspective is oversimplified and ignores the nuances of biological responses to diet. In fact, as discussed in detail in episode 71 of my podcast, this type of response can be likened to any macronutrient consumption—be it carbs causing insulin spikes or fats raising cholesterol levels. The issue isn’t the transient spikes themselves, which are natural post-meal responses, but rather chronic elevations that could pose health risks.

Moreover, if such temporary increases were truly detrimental, simple lifestyle adjustments like walking after meals or mindful eating could mitigate their effects—strategies that many, including diabetics, employ successfully. The alarmist view that any increase in blood markers is a health hazard only leads to extreme dietary strategies, like those practiced by individuals such as Hira Ratan Manek, who claimed to subsist on sunlight for decades—a claim both dangerous and debunked. Highlighting these extremes serves to illustrate the impracticality and irrationality of fearing normal dietary proteins based on transient biological responses. The key is balance and moderation, not elimination of essential nutrients.

The Dangers of Oversimplification

Articles and studies that demonize protein as a detriment to heart health often overlook its significant benefits in weight management and metabolic health. Experts widely recognize high-protein diets for their effectiveness in body recomposition and as a strategic tool in combating obesity, a major contributor to heart disease risk.

Much of this fear-mongering is based on results from studies using genetically modified mice, which may not directly translate to human health scenarios. While these findings are intriguing and provide a basis for further research, they do not warrant immediate concern for the general population. However, it’s worth noting that experts like Layne Norton have acknowledged the well-executed nature of these studies. These studies also highlight a strong correlation between higher protein intake and reduced body fat—underscoring that obesity poses a far greater risk to heart health than protein consumption ever could.

High-protein diets do more than build muscle; they play a crucial role in preventing the type of fat accumulation linked to numerous health problems.. Ironically, by focusing excessively on the supposed dangers of protein, we risk overlooking its role in offsetting a more dangerous condition: obesity. This cycle of fear around various macronutrients only contributes to dietary confusion, leading people to despair about healthy eating choices, ultimately driving them towards poorer dietary habits under the guise that “everything is bad.” This approach to nutrition is like stepping over dollars to pick up pennies, fixating on the minutiae while missing the bigger, more impactful picture.

Conclusion: The Need for Balanced Reporting

The debate over protein’s role in heart health is far from settled. Sensational headlines and studies with limited scope do little to inform the public about the complexities of nutrition and its impact on health. A balanced diet, tailored to individual health needs and lifestyle, remains the best approach to nutrition. Rather than fearing protein, a more nuanced discussion about diet quality and moderation in all things—including macronutrients—would serve the public’s health much better.

Final Note: A Call for Critical Thinking

As consumers of information, it’s essential to scrutinize health news and studies critically, acknowledging that not all research translates directly into practical dietary advice. By understanding the science behind the headlines, questioning the motives behind agenda-driven articles (“agendacles”), and consulting with healthcare providers, we can more effectively navigate the complex landscape of nutritional guidance.

This marks the third episode in which healthy dietary choices, particularly protein, are under scrutiny, with the last two episodes specifically targeting protein (episode 72 covers this specific article in depth)—and even more pointedly, a crucial amino acid within it: Leucine. Leucine is renowned for its benefits in health optimization and muscle growth. Interestingly, leucine is most abundantly found in animal-based foods—the very foods currently being advised against. This pattern raises concerns; my recent Twitter post touched on this, highlighting a growing trend in promoting plant-based and lab-grown meat alternatives, as previously discussed in Episode 57. It leads us to question: When did meat, a staple in the diet of many creatures for millennia, suddenly become vilified?

This coordinated shift away from traditional animal products towards alternatives isn’t just a dietary change—it’s a significant cultural shift that merits cautious evaluation. The demonization of leucine, a beneficial amino acid, appears to be a strategic move to sway public opinion, which begs further scrutiny about the motivations behind these dietary recommendations.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to hear more on this topic, you can watch this episode here “Why Is Protein Causing Heart Attacks?”